Jay Shuster from Pixar.

The title of the film Planes, Trains & Automobiles might just be the perfect description for Pixar Animation Studios sketch artist Jay Shuster’s childhood in Birmingham, Michigan. As the son of a car designer, Jay’s childhood bedroom was a nest of blue prints, drawings, posters, machines, and models of all things connected with nearly every mode of mechanized transportation.

But it wasn’t until Jay saw Star Wars that he connected his interests to a possible future in the film industry, where he saw an opportunity to work in an unrestrained creative culture. That desire initially took him to Lucasfilm Ltd., where he designed a variety of vehicles and environments for the Star Wars prequel film trilogy.

Jay arrived at Pixar Animation Studios in 2002 as a concept designer on Cars, where he translated Director John Lasseter’s ideas into characters and environments. He served the same role in Andrew Stanton’s Art Dept. on Disney/Pixar’s 2008 release, WALL•E. He is currently working on Cars 2. Jay’s Blog

Can you tell us a bit about Pixar and what it’s like to be part of the Art Department?

I’d say the best part about Pixar is: it’s removed from the movie-making world at large. It’s got its own ways of making these things not necessarily saying the most perfect or imperfect way; but it’s own way. the Art Dept. is composed of major talent like most art dept’s. Here, again, nothing new there. Apart from the projects that inspire the best out of the folks. For the most part no one’s attempting to climb over you to get somewhere- people are hired based on how well they play with others. And, of course, for their talents. The ‘playing well with others’ component may very well be more important. The first thing that hit me when I started at Pixar was the fever-pitch euphoria as the premier of the next film approached. It’s incredible to experience that company-wide optimism. Some folks may write it off as the effects of the ‘kool-ade’ but I think it’s a collective phenomenon of individuals reveling in their contribution; holding close what’s dear to them and taking pride in what they do. It’s a rare experience that’s being lost to the cultural-malady of entitlement and convenience. (Yeah, so I bust into a rant on the culture!) A loss of craft is to blame, as the manufacturing heritage of this country disappears. When people lose touch with their craft (whatever it is) ..they stop knowing where (or why or what) their purchases come from and, then, expect stuff to just appear out of no where. (okay, end of rant.) These movies are still crafted. They’re hard to make. Nothing comes for free- every surface of every character, prop and environment requires your full attention.. and happy accidents are few. Very committed people spend a high school diploma’s worth of time (sometimes years longer) on these films. I like working with committed people. There is no shortage of them at Pixar.

How would you describe your skill set and how it’s fit in with the different projects you’ve worked on at ILM and Pixar?

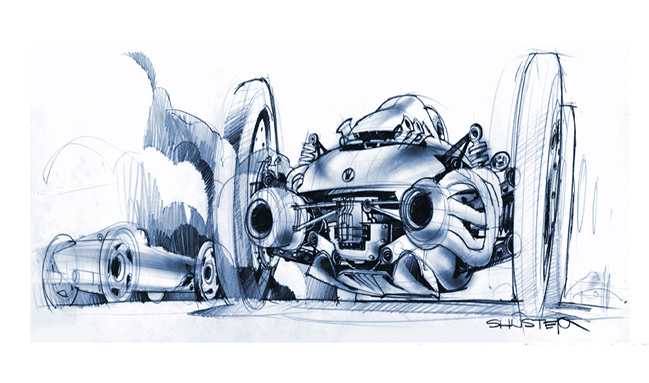

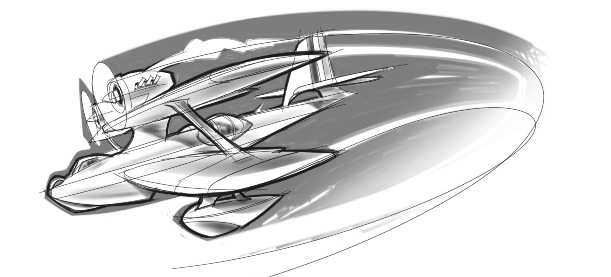

My personal skill set didn’t really find traction till getting the Pixar gig. I was way into the sci-fi thing as a kid and let that dictate my path for years, but didn’t feel fully comfortable in that skin when it came to the day-in, day-out of live-action feature film. Growing up in a manufacturing society such as Detroit, or (these days) any other post-industrial mecca, planted the seeds of purpose in design. The act of skinning over a machine with yet another variation on the theme had it’s day decades before. Kids will render the obligatory ship bristling with hardware and it’s cool and all, just.. lacking in something rooting it to that part of the brain that makes me care. So, Had i stayed in Detroit? Confronted with the similar routine of pinning a form to four wheels in a quarterly cycle? A quandary. At least every day out here was ‘casual dress day’ and there was the opportunity to replace the four wheels with 3-stage anti-grav gear and skids. My work on Star Wars connected the most with less-story-centric themes I mean; I really, really wanted to connect with the story of the film but, honestly, it just didn’t interest me that much. I was way into the design of these films. the design that jumped off the page in the original trilogy art-of books. The rock-solid, true-to-material McQuarrie designs that, you knew- you could tell, came from a guy who was once a draughtsman at Boeing. I contributed what I knew best: vehicular design in all its levitating, space-drama glory. I’d just come off a job back in Detroit a couple years before working for Roush Racing. They ran factory teams for NASCAR and SCCA Trans Am. It was, perhaps, the closest thing to the space-race in Detroit terms. So the designs for some of the pod-racers in Ep.1 was a windfall of familiarity. That was the high-water mark for my experience on that film and I embraced them with my own back-stories and made the few I worked on my own private Idaho. The Pod Race started life as a 6 or 7 lap race and narrowly escaped with 3: It could’ve afforded its own spin-off or mini-series. It could’ve floated the entire second act. (and third.) (and first.)

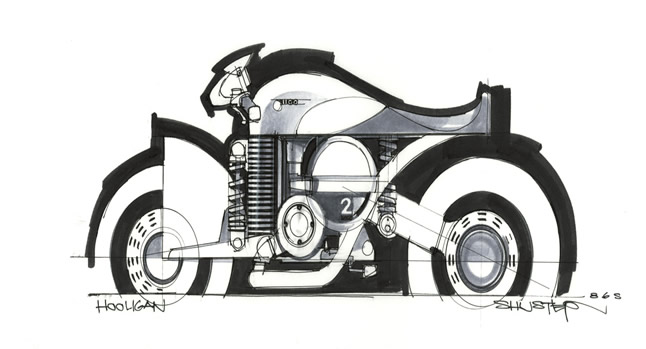

Going to school for Industrial Design afforded the greatest skills for the work I do. At that point the curriculums still involved manipulating raw materials and solid foundations in drawing. There’s much to be said for the cutting, forming, welding and spray booth arts. Feeling the weight of a block of high-density foam in your hand, visualizing a series of cuts, cutting into it with the right blade and pressure. Knowledge like this informs your ability to express in 2-D as well: to describe the world around you. Like Ralph McQuarrie’s rock-solid designs I mentioned above- by looking at the sketch you know immediately if someone knows how to apply that knowledge or is just imitating it.

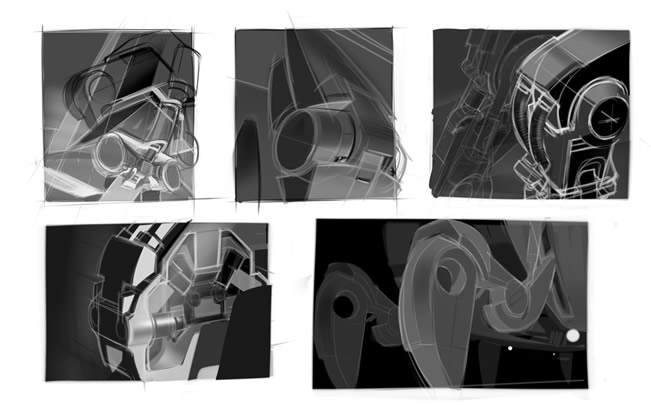

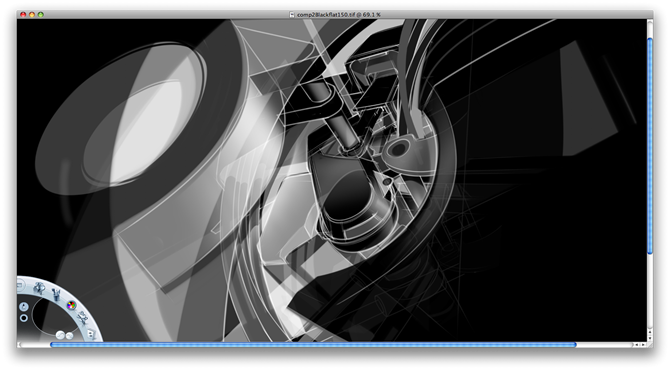

Part of the job at Pixar involves producing highly detailed model-packets of final designs to hand-off to the modeling folks. It’s a trick to translate loose character sketches into an orthographic format while keeping it on-model. One must forecast how the form evolves from one surface to the next- and it’s likely the drawings will never be spot-on accurate. The Model-packets function as a flag in the ground to base the next stage of production on. The hundred-page+ Wall-e model-packet was probably the most accurate I ever got due to the generous lead time and thought process expended.

3) Tell us about Wall E… What was involved with designing the main characters and what it means to you to be part of an Oscar winner?

The designs for Eve and Wall-e were a product of simultaneous close-collaboration and distant closed-door creativity. Andrew Stanton and the story team had been throwing around loose concepts during the initial writing of the film. Wall-e was a box with eyes on stalks and the treaded running gear. Eve was a floating egg. These broad strokes didn’t change. Andrew loved the cube-to-egg relationship of the characters. It nailed the essence of incompatibility between these two robots that weren’t ever supposed to share anything more than a brand of solder. The marching orders were passed down from on high: The robots had to functionally, physically work or damn-near-close. For Wall-e I was given the grocery list of the binocular eyes, a metamorphosing cube body and the appeal of a garbage compactor. Eve levitated, had womb stowage and the aesthetics of an Apple product. 1.5 years of iterative design process later two final designs were surrendered to animation. Surrendered: There’s always something more to be improved upon- it’s hard to let go. That said, I was lucky to have so much time to fixate on the details (alone at my drawing board). It was, also, a crazed interaction of story, design, animation and modeling that constantly redefined the character’s look and function. Each component pulling in their respective direction with good results: covering a lot of ground, solving problems and moving forward. A majority of the time.

Jack Black’s comments leading up to presenting Andrew Stanton with the Oscar for Wall-e were significant: you CAN bet your money on good film making. Trust the process and the people you work with. You don’t just write a screenplay and hand it off to a production facility. The screenplay doesn’t remain the same through to the end of the production process. The Wall-e in theaters was a completely different film from where it started years before. The process was recognized that night at the Oscar’s. It’s a long, most times, grueling ritual. And Wall-e was fully deserving of the recognition. I felt complete gratification.

4) Can you tell us a little about how you work? What tools do you use? Can you talk to “everything is a finished piece”.

Entirely iterative as mentioned above. It is a back-and-forth process of being pitched to and pitching-back ideas. Sketches remain loose (or as loose I can be). I draw everything free-hand and, these days, alternate between paper, SketchBook Pro and Photoshop. Whichever suits the task at hand: and the task at hand, currently, is under a compressed schedule. SO I am drawing straight into the PC with awesome results. Going back into existing files and overlaying iterations makes for rapid-fire conceptualization. Layers are priceless. I don’t modify the tools. The factory-installed pen, fat marker and air-brush are good enough. I’ll revert to paper for art reviews with the director when ideas are flying around the room.. brain-storms and the like.

When I draw/design I pretty much know what it is and how it’s composed on the page before I put pen-to-paper. There’s much mental footwork that allows this to happen- particularly knowing my subject inside and out. I like to crank through drawings. Things get laborious if I spend more than an hour on a given piece. Of course, there are those that require more time and energy.. but, generally, shorter times produce more concise ideas on paper.

5) Can you tell us anything about the projects that you are currently working on?

I’ve been working on CARS 2 for the last nine months. It is my first foray into art directing on a Pixar film and, so far, it’s an absolute hoot. The first CARS film was a complete joy so far as channeling my car-centric roots into three years of designing characters and environments. The art directing gig can be pressure but I’m getting equal amounts (drawing) board-time for every quarter-mile-worth of sprinting between offices of folks designing, building, rigging, painting and animating characters. It’s exactly where I want to be.

6) Staying fresh is always a challenge… Everyone at Pixar must be highly motivated in this aspect, so how do you keep yourself creative.

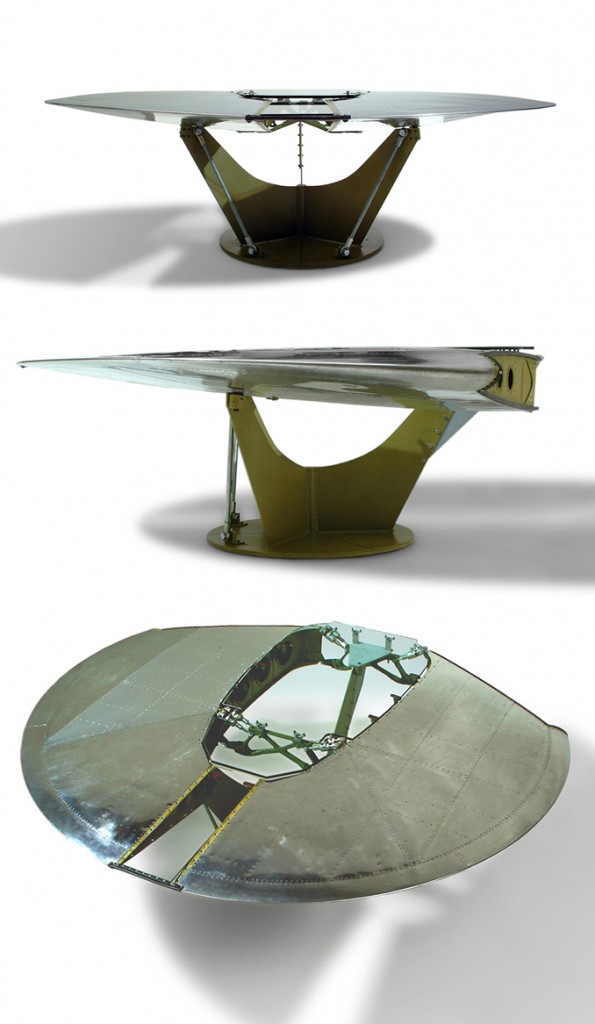

Work is, both, the thing that exhausts me AND keeps me going. I ask little of myself after hours these days though. I’m pretty much spent at the end of the day- satisfied that every line I laid down on screen or paper contributed. I have been making a concerted effort to keep the sketchbook full and current. The blog vaguely motivated the reason to draw more when I started that a year or so ago.. but I enjoy getting out and just drawing on location- for no reason at all. Apart from the idea drawing for ones self, generally, is known to keep one sane. Get too wrapped up in work and soon you get to feeling like a hollow husk of a human just pushing product. Defining yourself outside the confines of the work place is vital. Back in the mid-90’s I started building furniture and house wares out of airplane parts I discovered while investigating scrap yards during my work on Star Wars. Building with my hands is as important as drawing in 2-D. The manipulation of material informs my design brain. Music has also become a priority. Three guitars wait patiently.