Spyros Tsiounis from Lucas Films on Storyboarding.

You’ve worked on a number of great feature films and contributed to how the stories were told. Can you tell us a bit about how you got involved with story development?

I have been interested in story since the beginning. Nothing fascinates me more in all of life. Although my responsibilities at studios had initially been in animation and layout, I would often also get involved in story. In 2003, the recruiter at Dreamworks, who happened to be the same person that offered me my very first job in the industry, invited me to take a test for a position in their story department. I was asked to write a short story, based on a simple premise they assigned, fully board it and pitch it to an audience of some of the studio’s directors and producers. It went well. I got the job!

What’s the key to storyboarding? How do all the stakeholders work with storyboards and the artists?

The key to The hierarchy in productions varies depending on the project. Generally, a producer assembles a development team made of a screenwriter, a director an editor, and a handful of story artists. Ideally, the story artists and writer inspire one another and work together to compose the best possible content and visuals to tell a compelling story that fulfills the director’s vision within the producer’s limits. The editor then cuts the boards together, adds temporary sound, dialogue, and music and makes the “animatic”: a rough version of the movie that nevertheless gives a fairly clear idea of whether the story works and whether the project deserves the vast investment of time, effort, and money that is typical of feature films. If the story has problems at this first stage, it’s unlikely that it will improve while in production.

Can you give the readers a sense of the scale that is typically involved in story boarding a major feature film? What are the timelines like… How many pages are we talking about and how do revisions happen?

He, he. I’ve never bothered to look up the production numbers of how many storyboards are produced to work out an animated feature, but I could safely say: an ocean of them! It is not uncommon for 5 to 7 story artist, or more, to spend anywhere between 2 and 4 years to come up with the kind of story one sees in the final film. Telling a good story is difficult. Plus, in animation, you cannot just shoot footage, as in live action, then figure things out in the editing room and not use, say, 80% of what was shot. In animated productions you cannot afford to throw much finished animation away.

So, you’d better know exactly what visuals you need to tell the story, shot for shot, beforehand. That’s what storyboarding is essentially: editing the movie before production even starts. As for revisions, there is usually a series of approvals that sequences need to go through before they end up in the film. The story supervisor, the director, the editor, the producer, the studio executive can all send something back to be reworked. From my experience, as long as there is a very clear direction in a project, stories tend to evolve, and become more refined and sophisticated, the more times the story is told. That is not to be confused, though, with delays due to a lack of clear vision.

Can you tell us about any specific projects that you’ve worked and what it was like behind the scenes?

Right now I’m working on Clone Wars, which airs at Cartoon Network. Suffice it to say, it is a childhood fantasy taking flesh right before my eyes.The best part about it is the people I’m surrounded by. Everyone is super-talented, and there is such good chemistry in the team. Story artists are by nature compulsive entertainers so there’s never a dull moment.

What’s your personal workflow? What tools do you use in your creative process?

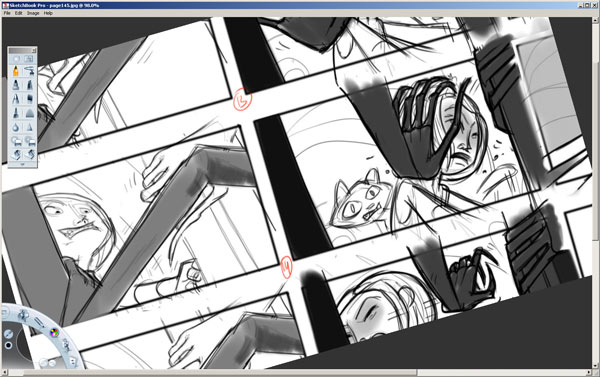

The story development process is becoming more digital. Since 2006, I have been working on tablets: first on tablet PCs, then on Cintiqs.

I mainly use Sketchbook Pro by Autodesk to draw boards. Of the software I have experimented with, it is the one I get the best line quality from. To put it in other words: it is difficult to tell whether a print out of drawings done on SKP was done digitally or with pencil and paper. And that’s the ideal: to be able to get a traditional look on top of all the benefits of a digital workflow, such as, being able to share large files quickly, easy to store large data, and, usually, easier to make revisions. Also, Sketchbook is a program focused on one thing: drawing. And it does it exceptionally well. For artists that do mostly that and do not care for unnecessary options, it makes for an uncluttered work environment.

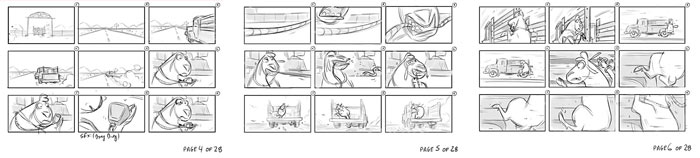

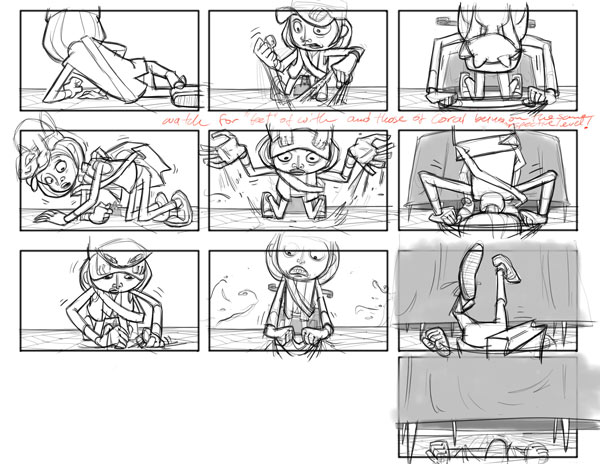

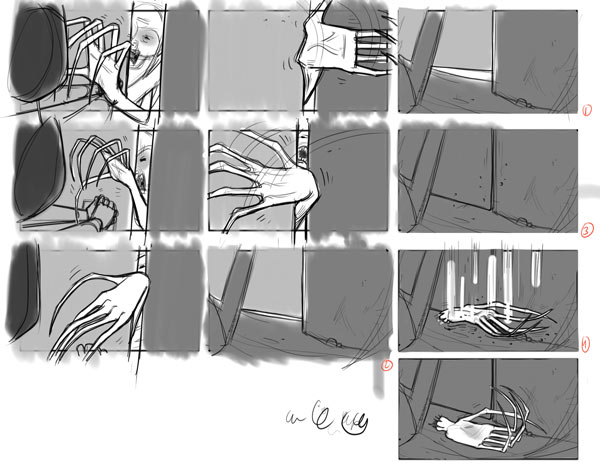

Personally, I prefer doing storyboards on a template of nine panels:

I draw from top to bottom first, then left to right:

Having nine panels in front of me, at any given time, helps me stay aware of how well they work with each other in continuity. Storyboarding is not about beautiful individual drawings. It’s about designing entire movie sequences that flow seamlessly. Individual panels play for just seconds. Or less. It is the entire story that matters.

As for “drawing from top to bottom”, I do it to better check how scenes “cut” with one another. A good cut depends a lot on where the point of interest is in one scene, and how well it passes the audience’s attention to the point of interest in the next. That is difficult to keep track of when drawing panels side-by-side, but readily obvious when panels are arranged vertically.

Technically, the best way to check on continuity would be to place on panel on top of the other. Same way a 2D animator flips through drawings. That’s how it plays in the final movie, after all. But then, you loose the overall view of the panels around it. After I am done boarding a sequence, I cut each individual panel out and get them arranged for presentation. By the way, I did not come up with this technique. I picked it up from a master story artist and director at Dreamworks: Simon Wells.

Nowadays, there are even more tools when it comes to previsualising a complex project. In some cases, I have seen no need for storyboards at all. In most, they are still indispensible. At the end of the day, the tools are becoming more and more sophisticated and so do the ways we tell visual stories. Whether, and to what extent, to use boards and/or computers depends on the nature of the individual project.

At the ranch: Spyros with Clone Wars supervising director, Dave Filoni, and R2-D2

Bio

Spyros has worked as a Story Artist on a number of successful feature films including: Flushed Away, Curious George, Kung Fu Panda, The Bee Movie, Coraline, Stuart Little, Stuart Little 2 and the not-yet released Shrek Forever After.

Currently working at Lucasfilm on George Lucas’ innovative television series Star Wars: The Clone Wars, he has also worked at DreamWorks Animation, Walt Disney Studios and Industrial Light and Magic, where he trained in computer animation.

He was layout supervisor on the feature film Rugrats Go Wild by Klasky Csupo.

Spyros moved to the United States from his native Greece as a 17-year old to take film classes at the University of Southern California and earn a BFA in Character Animation from the California Institute of the Arts. He was granted Permanent Resident status in the United States in 2005 based on extraordinary ability.